It was 9/11. The first plane hit pretty early in the day. That’s when it clicked for me — she flew out of Logan today.

“It was 9/11. The first plane hit pretty early in the day.” Navy flight engineer John Tappen remembers the terror he felt as a high school sophomore. “Every TV in the school was turned on, and they were playing the towers. That’s when it clicked for me.”

His mother had travel plans that day.

“My mother flew all the time. Then I thought, ‘Oh my god. She flew out of Logan today.”

“It wasn’t until I got out of Spanish class that I was able to try and call, and I couldn’t get ahold of anyone,” said Tappen. “The cell towers were shut down.”

After enduring a seemingly never-ending school day filled with panic and uncertainty, his father finally returned home to give word that his mother’s plane had been safely grounded. She was alive.

As a young boy, Tappen felt anger at the possibility of his loved ones being hurt.

“I sort of got a taste of what the whole world goes through on a daily basis,” Tappen said.

A Way Out

That terror coupled with his disinterest in school led him to look into careers within the military.

“School life was difficult for me,” said Tappen. “I felt like I was bored — I wasn’t being challenged. It was more fun to get people to laugh or to smile than it was to learn.”

The attacks on September 11 only solidified his choice to eventually enlist.

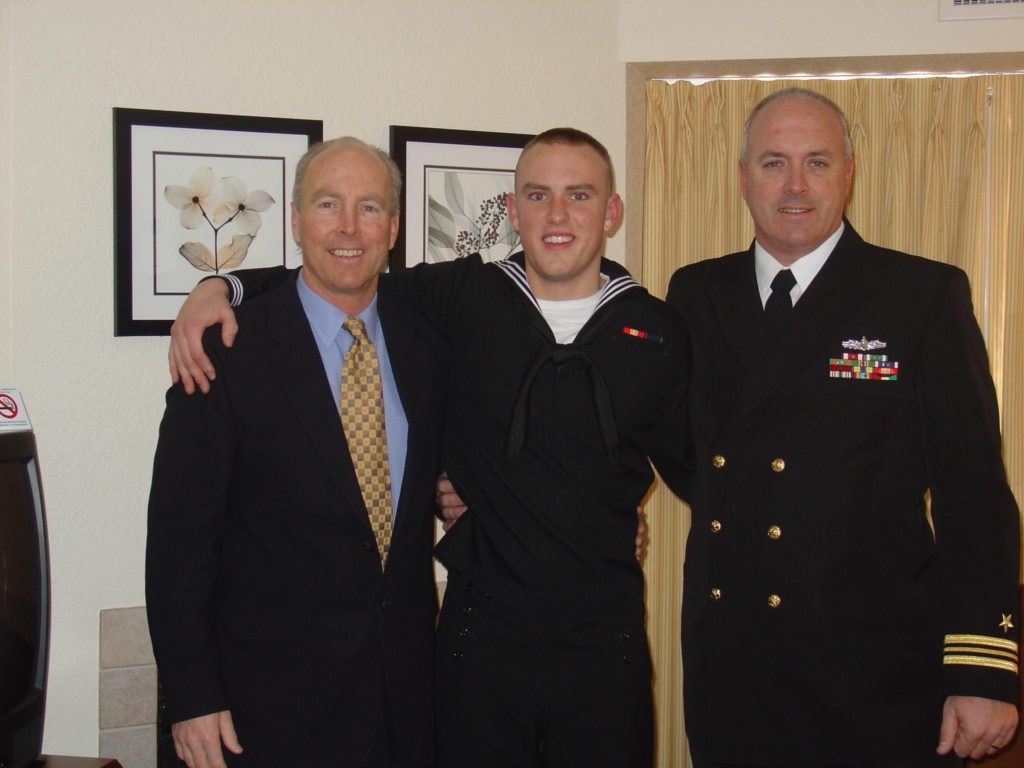

At age 18, Tappen packed his things and went to spend a summer in Norfolk, Virginia, with his uncle, a lieutenant commander. His uncle encouraged him to talk to the local Navy recruiter, and by 2006, he’d filled out his paperwork and enlisted in the United States Navy.

John’s father, Rob Tappen, remembers the feelings that arose upon his son’s enlistment.

“I had mixed emotions,” said Rob. “We’re a military family, so I was very proud that he was taking that route. I really thought it would straighten him out in a lot of ways — that level of discipline and the opportunities that he could pursue.”

For Tappen, it was an opportunity to find his place and use his talents for a greater purpose.

Having dreams of flying and scoring well on his military vocational assessment, he chose to become a flight engineer.

Not What He Signed Up For

“Before deployment, it felt good. I found my people. I got to wear a flight suit every day, and I was into it,” Tappen reflected. “After deployment, I felt dirty.”

“There would be bomb scares at the front gate,” Tappen said. “You’d be sprinting full speed away from what could potentially be an IED.”

“Those are things I didn’t sign up for. I never wanted to do any of that,” he said. “That’s when I think all of this started — being over there and seeing things I didn’t want to see.”

Tappen began leaning on coping mechanisms like self-medication to get through the daily turmoil.

This led to his eventual medical discharge.

“When I was getting high every day — that’s when I realized I shouldn’t be in the Navy anymore,” said Tappen. “I was in charge of people’s lives. I was more of a danger than I was a help.”

“At the time, there were only a few flight engineers in the Navy,” said Tappen. “It felt like I was part of a smaller group who was pushing the envelope.”

While in the Navy, Tappen served both domestically and on foreign soil.

“My duties included submarine hunting, drug busts — basically just being responsible for the crew members — making sure everyone got home safely and that the plane was in good condition,” said Tappen.

“You’re the first one there and last to leave.”

At first, Tappen thrived in his role within the Navy.

Until he was deployed to the Middle East in 2009.

A False Front

For Tappen, returning to civilian life was a shock to his system.

At first, he considered it a celebration, drinking and partying upon his return.

“Then, it turned into doing it every day for months on end,” Tappen said.

“It wasn’t celebrating. It was me not dealing with something. It was doing prescription pills and smoking weed every day, and I thought nothing of it.”

Tappen was living in the Northeast, and his immediate family had moved to Florida to be near grandchildren. The nearest reputable VA facility was over an hour from his home, and mental health was a taboo topic at the time.

He felt completely alone, but he made efforts to keep a façade of normalcy for those around him.

Unless you counted the number of Monsters I drank and the number of cigarettes I smoked, you wouldn't have known anything was up.

“Unless you counted the number of Monsters I drank and the number of cigarettes I smoked, you wouldn’t have known anything was up,” said Tappen.

“I lived in Fenway and made wonderful money, but none of that mattered. I was still drinking a ton,” he said. “I still felt empty and broken.”

Susan Tappen remembered the helpless feeling of watching her son isolate himself.

“He wouldn’t really tell us what was wrong, so we kept thinking ‘Let’s give him more time. Maybe it will get better,’” she said. “It didn’t get better.”

Despite being home, safe from war and insurgent attacks, Tappen’s mind was still stuck in combat-mode.

In order to cope with the daily hypervigilance and difficulty acclimating, Tappen turned to self-medication.

“That’s why people escape,” he said. “Because the reality in my head was nutzo.”

“If I got drunk or high, that reality was not as extreme. I could go out and not be as cynical, but that wasn’t me. That was alcohol and drugs. That’s not me being over anything — that’s just me pushing it down. And it eventually comes out in other horrible ways.”

Despite putting on a convincing front, occasional cracks would peak through, revealing the severeness of Tappen’s suffering.

“All of a sudden, he’s crying all the time — and not because something bad happens. It’s just out of the blue,” his mother remembers.

One day, while in line to check out at the local grocery store, Tappen suddenly broke down.

“I immediately started crying,” he remembers. “They weren’t even sad tears. I went to the car and freaked out. It was an involuntary experience. It wasn’t that I watched a sad movie. It was so random, and that scared me.”

“It was at that moment that I knew I needed to rearrange the cards a bit and try something new,” Tappen said.

Nothing had worked for him in the past. He was prescribed countless medications by the VA, turning him into a “zombie,” according to his parents.

It took years until Tappen began to find some reprieve in therapy.

In 2019, Tappen picked up and moved to Florida to be closer to his family, and soon after, he discovered K9s For Warriors through a fellow veteran.

“I wasn’t doing anything productive until 2018 when I realized I wasn’t happy,” Tappen said. “I started becoming much more honest. That started with therapy and eventually applying to K9s For Warriors.”

Am I "Broken Enough"?

At first, Tappen was hesitant to apply.

“I thought I wouldn’t qualify, and I didn’t want to be rejected again,” Tappen said. “I didn’t want to sign myself up to get let down.”

There was also a piece of Tappen that wondered if he truly needed a Service Dog.

“I thought ‘I have all my limbs. I have a good family. I take medication. I don’t drink nearly as much. I have a wonderful fiancé.’”

“I didn’t want to take a dog away from someone who needed it more,” Tappen said. “I didn’t want to take away from my fellow brothers and sisters in arms.”

Tappen found himself comparing his combat experiences to others,’ invalidating his own mental health needs.

“I haven’t had nearly as horrible experiences as some guys, but that could have been me very easily,” he said. “The bomb could have been me, and and I could have died. It puts those things in your head that were never going to be there before.”

With encouragement from his loved ones, Tappen filled out the K9s For Warriors application, and a few months later, he was paired with a poodle mix named Henry.

Life has never looked the same since.

An Instant Connection

“It was such a drastic change the moment I met that dog. It was absolutely love at first sight,” Tappen said. “It was the epitome of all the cheesy, corny stuff you see in the movies.”

“It was almost like this weight I didn’t even know I was carrying came off my shoulders.”

The pair trained for three weeks at the K9s For Warriors Gold Family Campus in Alachua County, Fla., strengthening their bond and learning to effectively communicate.

“The first week, I broke down,” Tappen rememebered. “I cried in front of grown men. I was so raw because I hadn’t handled the emotions. It all just came out.”

For Tappen and Henry, those three weeks were filled with learning and love.

“It was difficult at first learning to communicate with your dog,” Tappen said. “You both have two different languages, and you don’t always understand their signals all the time.”

For both, though, the hard work has paid off tenfold.

“Because of Henry, my son is more himself again. He’s more John,” Susan, Tappen’s mother said.

“He is more interested in his future — dreaming and having goals — rather than just existing,” added his father, Rob.

Since returning home, Tappen has begun going out more, not only to care for Henry, but also on his own volition.

“In this day and age, I can order anything to my house. It encourages self-isolation. You can use DoorDash or Amazon anytime — it’s great, but it encourages you to close yourself off,” Tappen said. “With a Service Dog, you no longer have that option.”

"It was such a drastic change the moment I met that dog. It was absolutely love at first sight."

Since having Henry, they started going on longer and longer walks together, eventually taking shopping trips for the whole family.

“You just don’t think of those mundane things when you’re going through life,” Tappen said. “But it’s really a big deal. Those are things that I’m able to do now because of Henry.”

Tappen now feels called to give back to the organization he says gave him his life back, telling his story to spread awareness of K9s For Warriors to other veterans in need.

He remembers the feelings that almost held him back from applying, and he now wants to keep other veterans from being bogged down in the same way that he was.

“You might be worse off than you think,” Tappen urged. “You are your own worst enemy sometimes. Sweeping things under the rug will only eat at you.”

With Henry by his side, Tappen feels like himself again, ready to weather whatever life throws their way, and he hopes other veterans will take the first step too.

“It’s indescribable,” he said of Service Dog Henry. “He’s my soul dog. I remember seeing that face, and it melts you. He is my fur rocket, and I am his human.”

"He's my soul dog. I remember seeing that face, and it melts you. He is my fur rocket, and I am his human."

Meet Henry

Henry was paired with veteran John at the K9s For Warriors Gold Family Campus in Alachua County, Florida.

John & Henry’s Graduation Date

April 22, 2021

Henry’s Sponsor

Florida Department of Veterans Affairs

Henry’s Background

Henry was lovingly donated by a family to become a Service Dog for a veteran in-need.

If you, or a veteran you know, are interested in applying for a Service Dog, start now.

Call the Veterans Crisis Line at 1-800-273-8255 and press 1 to speak with a qualified responder 24/7.